Get Out: "Now, you're in the sunken place"

About 9 years too late, but I finally weigh in.

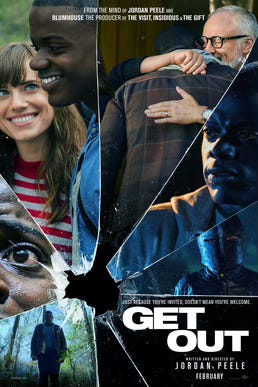

I acknowledge that horror is easily my least favorite film genre, and one that I generally eschew regarding my moviegoing. There are exceptions—The Exorcist is an outstanding film, as is Rosemary’s Baby and The Shining, just to name a few. Those are all films I enjoy and return to. But in the most general sense, it’s simply not a genre I enjoy, whether it’s the sensation of being scared or the gore associated with so many horror films. As a result, I was reluctant to watch Get Out, Jordan Peele’s 2017 directorial debut, and I missed seeing it during its initial theatrical run and its time at the center of our cultural conversation. Having since caught up with it, I regret not having seen it sooner. It’s an amazing directorial debut—a film I would not have expected to enjoy and yet I did. Though it certainly received praise upon its initial release, I feel like it deserved even more, specifically in the way of Academy recognition. Get Out will be one of the definitive films of the last 25 years and one that will be considered in a wide range of cultural and cinematic contexts.

What Peele does so well is to take a largely innocuous setting and fill it with such horror and dread. This affluent, large home in upstate New York that, in a different context, might be the setting for light-hearted leisure and entertainment. In that regard, Peele’s very much putting us in the shoes/behind the eyes of Chris (Daniel Kaluuya) who, as an African-American man, is accustomed to feeling out of place in environments that appear comfortable and normal to most—particularly white people. Peele, along with cinematographer Toby Oliver (whose largely worked in conventional horror), uses the camera to make you feel Chris’ outsiderness and to establish these visual cues that take on greater meaning after you’ve seen the film once. I think specifically about seeing Walter running at night along with the “Sunken place” and the final confrontation between Dean and Chris in the Coagula operating room as being much more visually interesting than one might expect.

The performances Peele draw out of his actors are also essential to the film’s effectiveness. Kaluuya, as the lead, brings the charisma and warmth that keeps you on his side, but he’s also enigmatic enough that he becomes a kind of cipher so we project onto him just as the gathering’s attendees project (in that case, it’s their desires). Bradley Whitford and Catherine Keener, playing Rose’s parents, are perfectly cast in the way they embody a polite, post-racial liberalism that conceals something deeply sinister. For those of us who love The West Wing, seeing Whitford—so closely associated with Josh Lyman—inhabit a role of such menace is particularly jarring. Keener, a frequent presence in the empathetic, humanistic films of Nicole Holofcener, is equally unsettling as a quietly controlling figure.

Allison Williams also plays against audience expectations, drawing on her reputation from Girls as she portrays Rose, Chris’s girlfriend. Lil Rel Howery provides the film much needed levity as Chris’ friend, Rod, which really stands out in this film of very restrained or intentionally off-putting performances. Rod functions as a clear audience surrogate, openly calling out the absurdity of the situation and remaining unequivocally on Chris’s side. While he may not add substantial thematic weight, his presence introduces a necessary levity that enhances the film’s overall balance.

What makes Get Out not just an entertaining film, or one that briefly captured national attention, is its ability to remain gripping while offering a sharp and perceptive commentary on race in contemporary America—particularly among those who consider themselves “progressive” (as exemplified by the line “I would have voted for Obama for a third term, if I could. Best President in my lifetime, hands down”). Peele asks the audience to challenge its assumptions and recognize that even amongst groups that believe themselves to be benevolent or enlightened, something insidious can lurk beneath. At the gathering at the Armitage house, the conversations between Chris and the party goers initially register as awkward, clumsy attempts of older white people trying to make polite conversation with a young African American man. Over time, they are revolted to be manifestations of a desire to own and a fetishization of the black body itself.

Peele melds together different subgenres—body horror, mad scientist, and the haunted house—in Get Out while also delivering commentary that avoids platitudes or simple reassurance. It’s a testament to this film’s achievement that it can operate on so many levels, and do so effectively, without sacrificing coherence or meaning. Like many others, I have been reflecting on the past 25 years of cinema and compiling mental lists of the best films from that period. While there may be some recency bias at play, or influence from the film’s continued praise, I believe Get Out unquestionably belongs on such a list. If not among one’s personal favorites, then certainly among the most important. There are few films that so successfully confront a subject as vast and complex as race in America while remaining propulsive and engrossing. Peele accomplished exactly that with Get Out.

I want to return to my initial point about my general dislike of horror, and how only a small number of films—The Exorcist and The Shining, among them—manage to break through for me. Get Out belongs firmly in that category. It earns this distinction because it is not concerned solely with fear or shock. While it certainly employs those elements, it offers far more beneath the surface, inviting sustained reflection and interpretation. That Peele accomplished this with his directorial debut places him immediately alongside some of the genre’s most accomplished filmmakers and establishes him as one of the most important new cinematic voices of his generation.

I'm with you on horror. I rarely seek it out. However, Get Out is one of the great films of the 21st Century. So layered, so well acted, and directed that it continues to deliver meaningful messages and idea.