"You don't beat it. You don't beat this river."

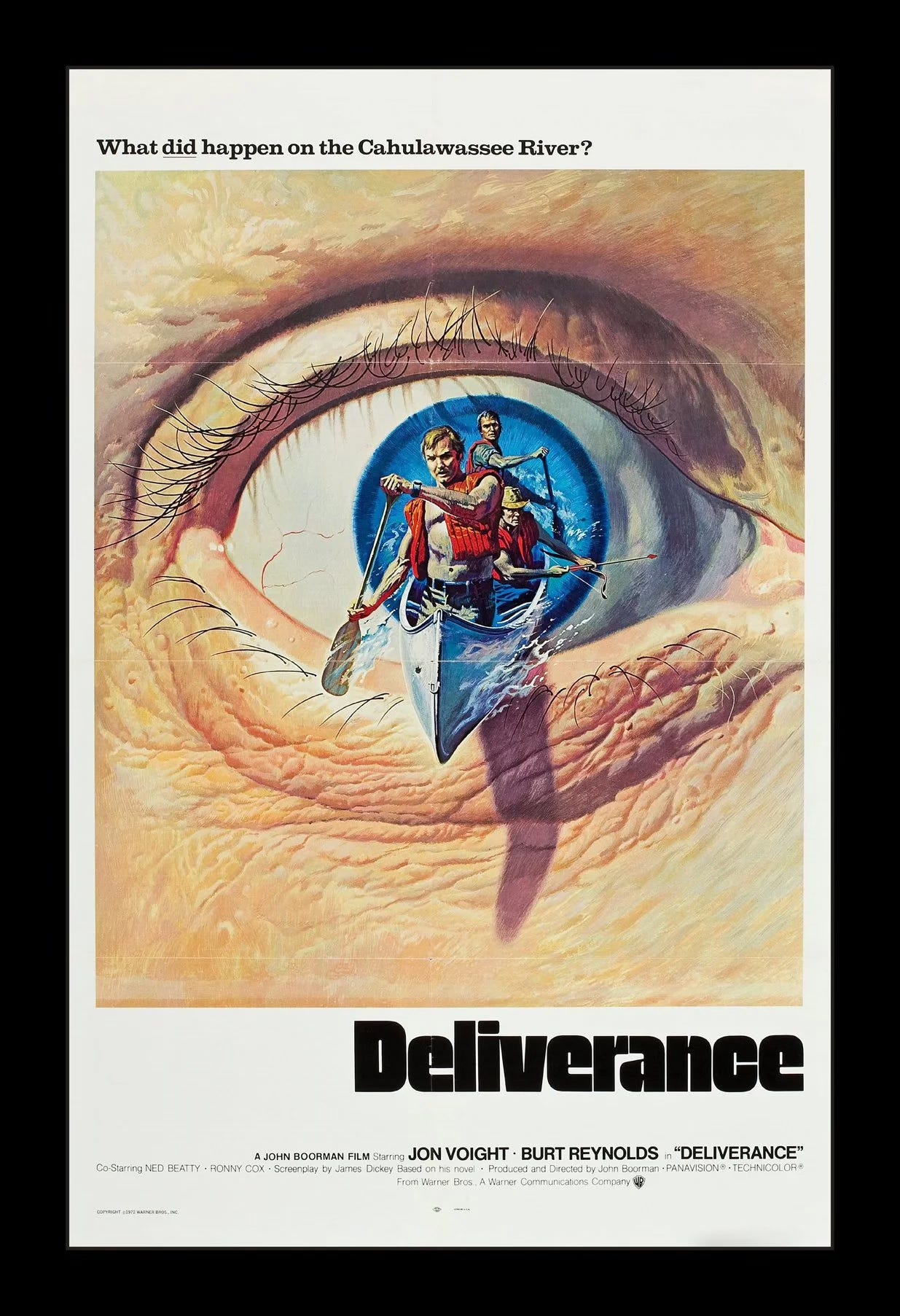

On finally watching Deliverance, and why we shouldn't reduce a film to just one or two simple things.

A text I often refer to and think about in my life as a teacher of literature is Cleanth Brooks’ “The Heresy of the Paraphrase.” In it, Brooks writes of how “a true poem is...an experience rather than any mere statement about experience or any mere abstraction from experience” and thus cannot be reduced to a paraphrase, something immediate and easily understandable. I’ll always say that a poem is not something to just be open, unlocked, and then when you find the answer you move along. You return to it, you find more in it, and it cannot be reduced to just a single lesson/moral/takeaway/punchline.

Unfortunately, I sometimes lapse into that kind of thinking (that once you “know” the most important thing, you can just move on) when it comes to films. There are plenty of films I’ve skipped over because I know what they’re “about” or what the most important thing is to take away about the movie. Falling into that camp is Deliverance, John Boorman’s 1972 film based on James Dickey’s 1970 novel. I knew about “Dueling Banjos” and the raping of Ned Beatty’s Bobby, and thus I didn’t feel like I really had to see it (I’d also read Dickey’s novel, and this is a pretty faithful adaptation—Dickey himself even wrote the screenplay and appears in the film). Despite my interest in the cinema of the 1970s, I just felt like I didn’t need (nor really wanted) to see it. However, after hearing the film discussed by quite a few people and taking a dive deeper into the films of that decade, I finally caught up with it.

Boorman makes sure to highlight the key concepts at the center of Dickey’s novel, which have to do with questions of masculinity and modernity versus the natural. Even before that pivotal scene, you get Lewis (played by Burt Reynolds) asserting the importance of adventure (“I never been insured in my life. I don’t believe in insurance. There’s no risk”) and reclaiming an essential, non-modernisized and civilized sense of one’s masculinity. I also think the dynamics of the four men on this canoeing trip—Lewis, Bobby, Ed, and Drew (played by Ronnie Cox)—and what they represent are all interesting commentaries on masculinity. Reynolds plays someone who is in many ways what you’d expect from a Burt Reynolds character (a heroic, adventuring figure), but that gets… if not subverted, then at least challenged in a way that would allow him to then really solidify that persona as his film career went on.

Beatty plays the “weak,” domesticated man in the wild just right and Cox as the artist comes across (Cox gets to show off his guitar-playing skills in the “Dueling Banjos” scene). Voight, as the man caught in the middle—civilized, but also closer to Lewis’ ideas and ideals in some respects—is strong as well and is another in his line of his great performances of the 1970s.

One thing that I really noted was the cinematography, which was by Vilmos Zsigmond (who later worked on 1978’s The Deer Hunter). You see the similar muted color pallet and the landscapes that you get in that film (I’m thinking of the hunting scenes in the pre-Vietnam section of that film). I think Boorman’s restraint as a director, telling a story that is a thrilling adventure story at its core, makes that visual style work a bit better (Cimino really lets things play out). That approach to cinematography, the naturalistic and muted, is quite apparent in that infamous scene featuring the rape of Bobby and the tying up of Jon Voight’s Ed. Things play out for longer than you would expect and you don’t cut away from it as much as you’d think. Again, this is a film that Tarantino writes about in Cinema Speculation and certainly you can see its influence on Pulp Fiction. The scenery, with this film done on location in Raburn County, Georgia (where the film is to take place) is really remarkable and the kind of thing you just don’t see anymore. It’s a cliche to describe the location as a character in a film, but it really and truly is with Deliverance.

Deliverance is a film that proven to be quite influential and relevant for cinema going forward. Whether it’s the idea of the excursion gone wrong, the depictions of the rural space as one filled with horror, these ideas keep popping. But it really is a testament to how a film is not and cannot just be reduced to just one thing, one scene, and if you know it you know it all. For one thing, the performances and the craft (the cinematography and editing) would be lost. Additionally, this film is about so much more than the horror of the “squeal like a pig” scene. These concerns about masculinity, modernity, and the wilderness are the stuff of great literature. I’ve thought a bit about Tarantino’s connections to Hemingway, but I’m intrigued if there’s a way to triangulate his interest in this film and how Dickey’s narrative was influenced by/connected to Hemingway (I would be willing to bet anything Dickey’s got some kind of connection to Papa).

There are certainly moments in Deliverance that don’t hold up—where the tone isn’t right or the technology takes us out of it (I’m thinking about Ed’s climb up the rock face and some of the day-for-night filming) or something just doesn’t work (a lot of the Drew stuff/his death doesn’t seem to work). But it’s an important film—for Boorman, for Reynolds, for Voight, and ended up being so for Tarantino and other directors. It’s one that took me a while to commit to watching, but ultimately I’m glad I did. Though I don’t think it’s a film I could ever teach given what transpires, I do think there’s a lot about the film that’s interesting to think about and that elevates it from being something so generic or exploitative.